The title, Plato and the Nerd, puts into opposition the notion that knowledge, and hence technology, consists of Platonic Ideals that exist independent of humans and is discovered by humans, and an opposing notion that humans create rather than discover knowledge and technology. The nerd in the title is a creative force, subjective and even quirky, and not an objective miner of preexisting truths.

The title was inspired by the wonderful book by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan, who titled a section of his prologue "Plato and the Nerd." Taleb talks about "Platonicity" as "the desire to cut reality into crisp shapes." Taleb laments the ensuing specialization and points out that such specialization blinds us to extraordinary events, which he calls "black swans." Following Taleb, a theme of my book is that technical disciplines are also vulnerable to excessive specialization; each specialty unwittingly adopts paradigms that turn the specialty into a slow-moving culture that resists rather than promotes innovation.

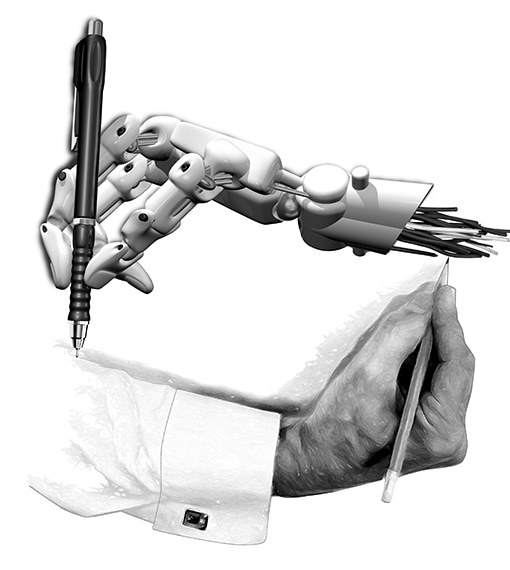

The image on the cover is inspired by M.C. Escher's famous 1948 lithograph called Drawing Hands. Escher's image shows two human hands bringing each other into existence by drawing each other on a page. Escher's drawing suggests a bootstrapping of humans, not just in a biological sense, but more in a sociological sense, as suggested by the elegant French cuffs adorning the two wrists in his lithograph. This is not just about humans creating humans through procreation, but rather more about humans creating humans by defining culture. In my version of the image, the robot hand is modified from an image by the illustrator Paul Fleet, and the human hand is a photograph of my own hand re-rendered as a drawing.

Humans are unique among animals found in nature in their reliance on technology. The French cuffs in Escher's lithograph represent a technology, albeit a rather old one, that is as much a part of being human as our biology and our languages. Humans do not do well in the wild without clothing, but clothing extends well beyond mere protection against the elements to become part of identity and social standing. Today, there is much more technology than just clothing that defines who we are. In our current form, I have to argue that technology brings humans into existence as much as humans bring technology into existence.

In Plato and the Nerd, several themes emerge that echo the sort of self-referentiality in Escher's image. Chapter 5 talks about how software encodes its own paradigms, an idea that would be better represented by one robot hand drawing another robot hand. The 20th century Turing and Gödel notions of incompleteness discussed in chapters 8 and 9 arise from the ability of software and formal models, respectively, to talk about themselves. Chapter 10 talks about how the notion of determinism in the physical world depends on an ability to construct predictive models that must exist within the very physical world that they predict. But each of these examples is symmetric, like Escher's image, where one component is bringing into existence another like component that is in turn bringing the first component into existence.

The cover image depicts an asymmetric cycle, a synergistic bootstrapping of unlike components. Chapters 7, 8, and 9 build a story that humans and digital technology, contrary the stronger claims of artificial intelligence, are quite unlike one another. Instead of mirroring one another, they are instead synergistically coevolving. This coevolution is seen very clearly in the strong effects that technology has on society and culture.

This is not much a coevolution in the biological sense. That sense would imply that technology is turning humans into biologically different animals with different DNA. Technology does have some effect on DNA, insofar as it affects breeding habits, infant mortality, and fertility, but these effects pale by comparison with its effect on culture. If you believe, as I do, that our human identity is as much cultural as biological, then most certainly technology is affecting our evolution.

I am convinced, nevertheless, that our symbiosis with technology is primitive compared to what it will be in the not-to-distant future. Technology today is like gut bacteria, in that we rely on it and it relies on us, but the relationship is hugely asymmetric. The cognitive and creative abilities of humans still vastly outstrip those of machines in many dimensions, and the machines still exist under the control of humans. But our dependence on the machines is at least as strong as our dependence on our gut bacteria. Just think what would happen to our society if we were to suddenly kill all the computers. It is far from assured that the patient (our society and culture) would survive.

This book is very much about the asymmetries of the relationship between humans and technology and about how technology is defining humanity while humanity is defining technology. Reflecting this asymmetry, notice that the robot is using a precision technical pen, and yet the human hand is a soft pencil drawing, whereas the human is using a pencil, and yet the robot hand is a computer generated hard edged image. This reflects the opposition between the soft organic wetwear that comprises human culture and the metallic, crystalline hardware that comprises digital technology. Chapter 4 talks about this hard and soft dichotomy, illustrating it with the impermanence of hardware in contrast to the much more durable ideas embodied in the hardware. More deeply, chapter 9 talks about the weakness of formal models when one strips them of the human interpretations of those models.

To our knowledge, humans are unique in nature in our reliance on and development of technology. Think about the primitive technology of clothing, represented by Escher's French cuffs. Where else in nature can we find creatures who augment their own bodies with accessories they make themselves that have become essential to their survival and central to their culture? The humble hermit crab "clothes" himself, but with scavenged shells made by another creature, a snail. The hermit crab has no hand in the creation of the technology, the shell, that he depends on. There is no cycle. Only humans have such a cycle.

The title was inspired by the wonderful book by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan, who titled a section of his prologue "Plato and the Nerd." Taleb talks about "Platonicity" as "the desire to cut reality into crisp shapes." Taleb laments the ensuing specialization and points out that such specialization blinds us to extraordinary events, which he calls "black swans." Following Taleb, a theme of my book is that technical disciplines are also vulnerable to excessive specialization; each specialty unwittingly adopts paradigms that turn the specialty into a slow-moving culture that resists rather than promotes innovation.

The image on the cover is inspired by M.C. Escher's famous 1948 lithograph called Drawing Hands. Escher's image shows two human hands bringing each other into existence by drawing each other on a page. Escher's drawing suggests a bootstrapping of humans, not just in a biological sense, but more in a sociological sense, as suggested by the elegant French cuffs adorning the two wrists in his lithograph. This is not just about humans creating humans through procreation, but rather more about humans creating humans by defining culture. In my version of the image, the robot hand is modified from an image by the illustrator Paul Fleet, and the human hand is a photograph of my own hand re-rendered as a drawing.

Humans are unique among animals found in nature in their reliance on technology. The French cuffs in Escher's lithograph represent a technology, albeit a rather old one, that is as much a part of being human as our biology and our languages. Humans do not do well in the wild without clothing, but clothing extends well beyond mere protection against the elements to become part of identity and social standing. Today, there is much more technology than just clothing that defines who we are. In our current form, I have to argue that technology brings humans into existence as much as humans bring technology into existence.

In Plato and the Nerd, several themes emerge that echo the sort of self-referentiality in Escher's image. Chapter 5 talks about how software encodes its own paradigms, an idea that would be better represented by one robot hand drawing another robot hand. The 20th century Turing and Gödel notions of incompleteness discussed in chapters 8 and 9 arise from the ability of software and formal models, respectively, to talk about themselves. Chapter 10 talks about how the notion of determinism in the physical world depends on an ability to construct predictive models that must exist within the very physical world that they predict. But each of these examples is symmetric, like Escher's image, where one component is bringing into existence another like component that is in turn bringing the first component into existence.

The cover image depicts an asymmetric cycle, a synergistic bootstrapping of unlike components. Chapters 7, 8, and 9 build a story that humans and digital technology, contrary the stronger claims of artificial intelligence, are quite unlike one another. Instead of mirroring one another, they are instead synergistically coevolving. This coevolution is seen very clearly in the strong effects that technology has on society and culture.

This is not much a coevolution in the biological sense. That sense would imply that technology is turning humans into biologically different animals with different DNA. Technology does have some effect on DNA, insofar as it affects breeding habits, infant mortality, and fertility, but these effects pale by comparison with its effect on culture. If you believe, as I do, that our human identity is as much cultural as biological, then most certainly technology is affecting our evolution.

I am convinced, nevertheless, that our symbiosis with technology is primitive compared to what it will be in the not-to-distant future. Technology today is like gut bacteria, in that we rely on it and it relies on us, but the relationship is hugely asymmetric. The cognitive and creative abilities of humans still vastly outstrip those of machines in many dimensions, and the machines still exist under the control of humans. But our dependence on the machines is at least as strong as our dependence on our gut bacteria. Just think what would happen to our society if we were to suddenly kill all the computers. It is far from assured that the patient (our society and culture) would survive.

This book is very much about the asymmetries of the relationship between humans and technology and about how technology is defining humanity while humanity is defining technology. Reflecting this asymmetry, notice that the robot is using a precision technical pen, and yet the human hand is a soft pencil drawing, whereas the human is using a pencil, and yet the robot hand is a computer generated hard edged image. This reflects the opposition between the soft organic wetwear that comprises human culture and the metallic, crystalline hardware that comprises digital technology. Chapter 4 talks about this hard and soft dichotomy, illustrating it with the impermanence of hardware in contrast to the much more durable ideas embodied in the hardware. More deeply, chapter 9 talks about the weakness of formal models when one strips them of the human interpretations of those models.

To our knowledge, humans are unique in nature in our reliance on and development of technology. Think about the primitive technology of clothing, represented by Escher's French cuffs. Where else in nature can we find creatures who augment their own bodies with accessories they make themselves that have become essential to their survival and central to their culture? The humble hermit crab "clothes" himself, but with scavenged shells made by another creature, a snail. The hermit crab has no hand in the creation of the technology, the shell, that he depends on. There is no cycle. Only humans have such a cycle.